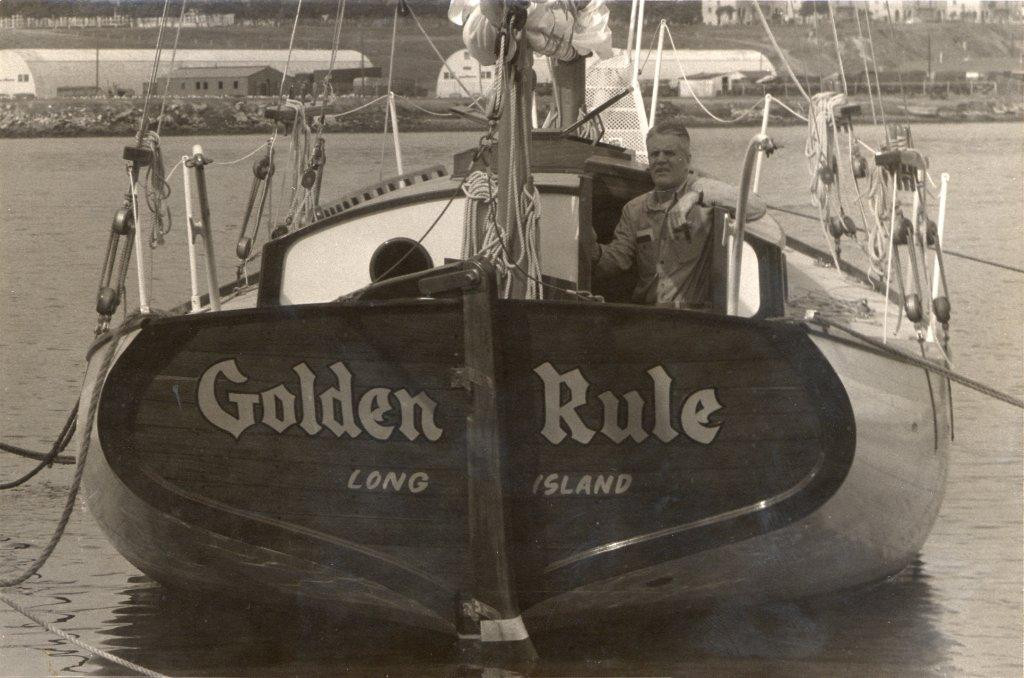

The Golden Rule was the very first of the environmental and peace vessels to go to sea. In 1958, a crew of anti-nuclear weapons activists set sail aboard her in an attempt to interpose themselves and the boat between the U.S. Government and its atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean.

At that time both the U.S. and the Soviet Union were conducting aboveground tests of very large nuclear weapons, which produced readily detectable clouds of radioactive fallout that wafted around the planet. Radiation contamination began to turn up in cows’ and mothers’ milk. Public concern grew, and for the first time many middle-class Americans began to wonder if their government knew what it was doing.

In 1958, the Golden Rule sailed from San Pedro toward the U.S. nuclear test zone at Eniwetok atoll in the Marshall Islands, but she never made it that far. The first time out of San Pedro Capt. Albert Bigelow, George Willoughby, William Huntington and David Gale were aboard. A week into the voyage the starboard jaw of the gaff broke. The repair was done, but a gale, the worse in twenty years, quickly followed. “David Gale was gravely ill. It was several days since he had even tried to eat or drink and we had given up trying to tell him to do so.” Twice the Coast Guard offered help and could have taken him to shore. Ultimately, Bigelow made the decision to turn back, knowing that the effort to stop the atomic tests might be sacrificed. They made it back to San Pedro two weeks after starting.

On March 25 they sailed again. Orion Sherwood took David Gale’s place. The weather was much better as they made their way to Honolulu.

She was twice boarded by the U.S. Coast Guard at Hawaii, and the crew were arrested, tried, and jailed in Honolulu. But, far from being defeated, their example helped to ignite a storm of world-wide public outrage against nuclear weapons that resulted in the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963, and which has continued down to the present in the many organizations still working to abolish weapons of mass destruction.

The example set by the Golden Rule and her crew was also the inspiration for subsequent environmental and peace voyagers and craft that followed in her wake including the Phoenix of Hiroshima, and later Greenpeace and the Sea Shepherds.

The 50-foot Colin Archer-style ketch Phoenix of Hiroshima, whose owners met Albert S. Bigelow and his crew in Honolulu, was the next boat to carry the mission forward. She sailed to the Marshalls that same year and successfully entered the test zone in protest. The horrors of nuclear war were issues close to the heart of the Phoenix’s skipper, Dr. Earle L. Reynolds. He had been sent to Hiroshima by the U.S. government after World War II to study the effects of nuclear fallout on the growth and development of surviving Japanese children, and was deeply affected by the experience.

The connection to the environmental organization Greenpeace is direct. At a Vancouver meeting of activists in the late 1960s, Marie Bohlen, an American inspired by the Golden Rule’s exploits, suggested a protest voyage toward the U.S. nuclear test site in the Aleutian Islands. The rusty trawler Phyllis Cormack, renamed Greenpeace for the protest, soon headed north and Greenpeace was launched.

Just as importantly, the use of nonviolent direct action as a basic guiding principle of the Golden Rule’s crew would also influence future generations of activists. The seas of the world have never been quite the same since.

It is in their memory of her crew, and the causes that they helped to inspire, that the Veterans For Peace have vowed that the Golden Rule shall again ride the waves of peace.

The Original Crew

A former U.S. naval lieutenant commander, Bigelow was among those most alarmed by nuclear weapons. In 1945, he had had a moment of epiphany when he heard the news of the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima. “It was then,” he recalled, “that I realized for the first time that morally war is impossible.” Later, in the 1950s, he joined the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and adopted their principles of nonviolence.

Bigelow had also been deeply affected by his family’s experience hosting several of the “Hiroshima Maidens,” women who had come to the U.S. for medical treatment after being terribly injured in the nuclear blasts over Japan in 1945. Bigelow firmly believed that the nuclear arms race was nothing more than a “race to extinction” that had to be stopped.

Deciding that action was called for, he and others joined the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) in 1957. At first, SANE went through normal channels, petitioning the U.S. Government and requesting meetings with officials. When that strategy brought no result, it was decided that more direct action was called for. Thus was born the voyage of the Golden Rule, and the age of the modern protest vessel.

In keeping with their Quaker beliefs, Bigelow and the others came up with what was then a novel approach: they would sail a small craft into the test zone in the Marshall Islands, risking their own lives to do so. At the same time, they determined that their protest would not be done in secret, but in the full light of day; and that a basic principle of their actions should be the fullest respect for the humanity of their opponents. In January of 1958, they wrote President Eisenhower of their plans.

“How do you reach men,” Bigelow wrote, “when all the horror is in the fact that they feel no horror? It requires, we believe, the kind of effort and sacrifice that we now undertake.”

It is easy to focus on Bigelow when describing the voyage of the Golden Rule. He was, after all, the author of the book by that name. But he would have been the first to point out that the other crew members were noteworthy in their own right, and that was indeed the case.

William Huntington was an architect, a Quaker, an international aid official with the American Friends Service Committee, and a Quaker representative to the United Nations. He had been a conscientious objector during World War II and was an experienced sailor. George Willoughby was also a well-known peace activist, a nonviolent war resister who seemed always to be at the center of the action. He went on to co-found Peace Brigades International and the Philadelphia-based Movement for a New Society, dedicated to nonviolent social transformation.

At 28 years of age, Orion Sherwood was the youngest of the Golden Rule’s crew, and the only Methodist. Prior to that, he had been a teacher at a Friends school in Poughkeepsie, New York. Known for his gentle disposition, he was also a graduate engineer, and had studied for the ministry. After the voyage, he returned to teaching at a Friends school in New Hampshire.